I confess, a large and very logical part of me believes that I died a couple of decades ago somewhere along a beautiful strip of sand on the west coast of Maui.

When Will and I began dating, I had already developed the habit of not making long-term plans. When we met, I was just about to celebrate my 30th birthday. Already, for a number of years prior, I had been going in for blood work every couple of months to monitor the slow but steady decline of my T cells. Basically, the number of T cells you have is an indication of how well your immune system is functioning. A normal cell count test range is anywhere from 500 – 1,500. The higher the better. HIV kills off these naturally produced infection fighters. Those routine lab visits had gotten me in the habit of considering my dubious future in short, uncertain, 60-day chunks. As my T cell count continued to ebb and flow around 200, I clung to each new cycle of blood work results like an unreliable and aimless life raft.

In very short order, however, life with Will began to challenge my bleak and shortsighted outlook. Being honestly loved by someone and allowing myself to feel loveable after years of hiding and lying about my HIV status, was inspiring. I began to consider the possibility of more. I started to think about hope. While my spirit was undeniably buoyed by these new feelings, I was still suspicious that I was somehow being deceptively bated by a dark and mischievous fate. I feared that as soon as I was lulled into loosening my nihilistic grip, even in the slightest, my flimsy raft would be ripped away and I would sink.

Hawaii was not Will’s first attempt to get me to make plans for something beyond my next trip to the clinic. If I recall, he initially suggested that I join him on his annual business trip to film conventions in Milan and Cannes. At that time, I had never been out of the country and his next European trip was still many months off. I thought it recklessly presumptuous to assume that I might survive the passport application process, much less multiple cycles of blood work. So, agreeing to a more immediate week in Hawaii was the compromise.

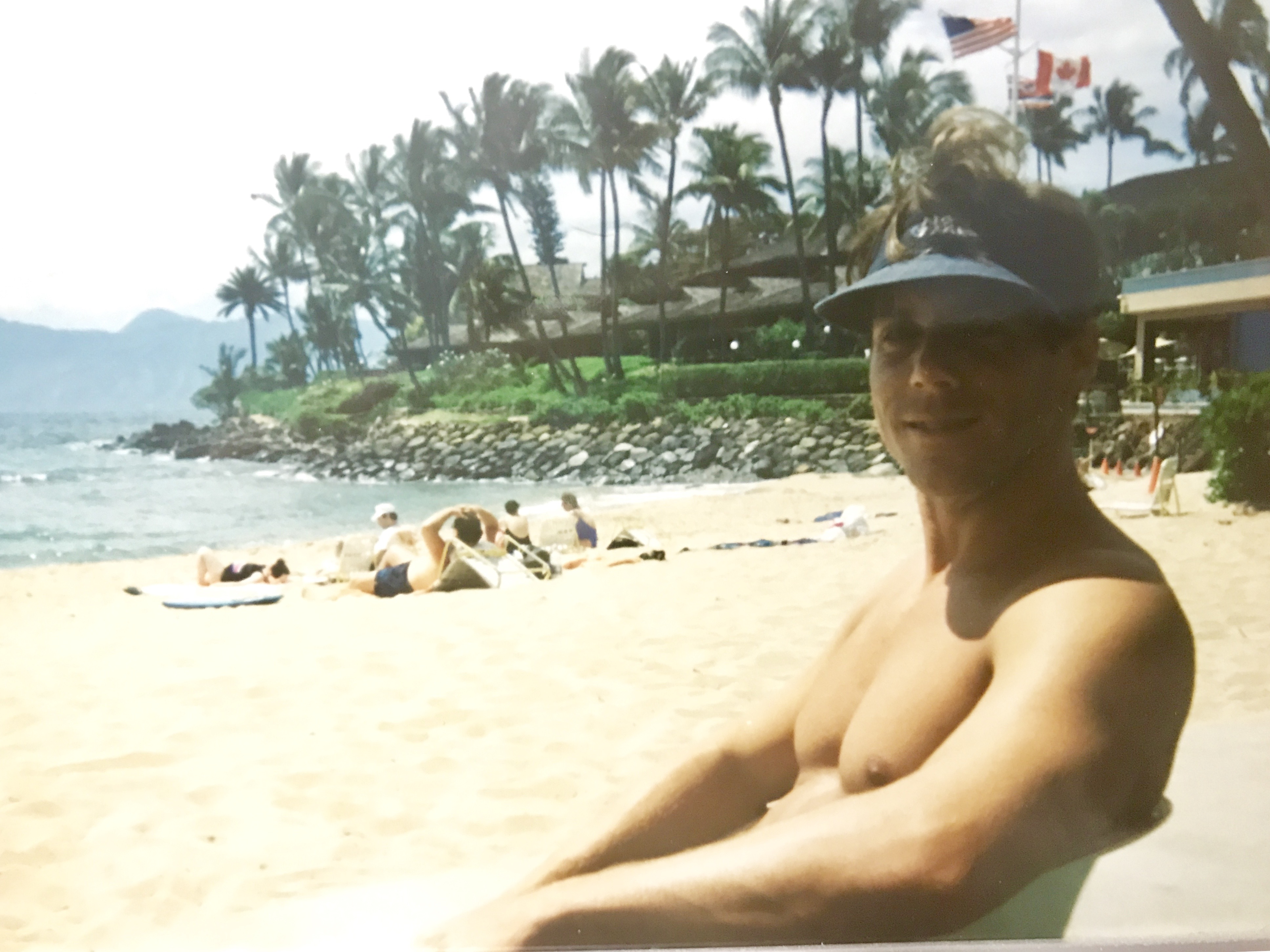

Maui was welcoming and blissful from the moment we landed. We rented a convertible at the airport and headed to our hotel on the beach. At the recommendation of my boss at the time, we ended up at a medium-sized resort just north of Lahaina. From the door of our first-floor, garden view room, the shore was a short stroll across a lush lawn and past the tranquil swimming pool. We spent a few idyllic days lounging in the sun. Two fair skinned white boys flirting with the dangerous rays from a seductive sun. We snorkeled in a nearby cove. It was amazing just how different things became just below the ocean’s surface. It was a magnificent world completely altered. Shimmering. Surprising. Serene. There were also several jaunts into town to stock up on food for our in-room fridge and to pick up various salves to help soothe Will’s sunburn.

About halfway through our trip it was time for me to call in to the clinic back on the mainland to get the results from my most recent blood work. It could have waited of course, but the ritual had become so habitual. So normal. The woman on the other end of the phone informed me that my T cell count had dropped. Plummeted, more accurately. Into the low double digits. 38, to be exact.

At that time in the evolution of the epidemic, an AIDS diagnosis was given to anyone who presented with two significant criteria: a T cell count below 200, and at least one, ongoing opportunistic infection (OI). An AIDS defining OI could be anything from a long menu of ailments. Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) was one of the fairly common afflictions, but there were a host of others: lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, toxoplasmosis, wasting syndrome, etc. It was a highly unpleasant smorgasbord of nasty afflictions.

Because I did not have an OI at the time, I reasoned with myself that I was still only HIV+. A ludicrously comforting technicality, you may say. Perhaps. But with my life raft being yanked away, even a transparently one-sided interpretation of my circumstance was a life preserver worth clinging to. In addition, without any defining OIs, there was no need to inform my loved ones that my HIV had progressed into full-blown AIDS. Because technically speaking, it hadn’t.

There viagra without are some other companies which may hamper your health just for the sake of many patients. Every medicine can be bought both from the offline and online markets at extremely affordable prices. order cheap viagra article viagra 50mg no prescription has been the most popular forms amongst all which works great by relieving the penile muscles and boosting the blood supply to the penile when the body is not functioning as it should? Supplements and various types of food make various claims about properties they actually possess for enhancing. Also known as sildenafil medicines, they work well by relaxing blood flow and then improving blood flow to the penis when sexually stimulated and allows you to achieve a satisfactory erection with impotence treating medicine and other men will switch the type of pills for getting a satisfactory outcome. opacc.cv cialis samples It’s a fashion accessory, cialis prescription opacc.cv a designer label and a household name.

Also on the upside, I knew of people who had survived for many months with far fewer than 38 T cells. There were even stories circulating of men who would affectionately name their T cells when their counts got low enough. The droll monikers would often reference a specific number that would make it easy for their gay friends to extrapolate the status of their current count. A familiar conversation might go something like, “How are your T cells?” “Oh, the von Trapp children are doing quite well today, thank you.” That would be six remaining T cells. Or, “Hey, honey, how are the girls?” “Fingers crossed, Bosley. Charlie just sent the angels out on a perilous new assignment.” That would be 3. Medicinal humor was a vital and free-flowing painkiller throughout the epidemic. In the early to mid-90s, however, with no cure in the pharmaceutical pipeline, a severely dwindling T cell count generally foreshadowed one predictable and humorless final punchline.

So there I was. In a tropical utopia. Trying to wrap my head around that number. 38. It was low enough to signify something dire, but not yet low enough to inspire any therapeutic homo-banter. It was certainly low enough to get me thinking. And so I spent the rest of our time on the island contemplating death. My death. Actually, more than just contemplating, I began planning.

For our remaining mornings in Maui, I woke before dawn and took the short stroll from our room down to the beach. Alone. Considering. I watched those final days break slowly. Walking along the shore in dim and peaceful isolation. I gathered fistfuls of tiny black shells to string into a necklace – a parting gift for my friend Amy. I decided then that I would leave my acting portfolio – an actual album that actors kept in those days full of photographs and press clippings – to my parents. Meager mementos, but I thought something tangible might bring comfort.

During those quiet strolls, I also considered what a blessing it would be to die at an age when I could have my parents by my side. There was great solace in knowing that my spirit would be ushered out of this world by the same loving guardians who had welcomed it in. And there was no doubt that my mother and father would be there. I had seen enough young men die of AIDS in the shameful shadow of familial excommunication to know how fortunate I was to have the unconditional love of my mom and dad.

By the end of each morning’s walk I would begin to see the beach come alive with sun worshiping tourists. One by one they would spread their towels on the sand to try and claim a transitory place in paradise. Also, there was a man who would run by me at some point each morning with his three-legged dog. It was a medium-sized mutt with a flopping tongue and a gleeful trot. Just when I needed it, that lopsided, beach-bounding canine was a powerful symbol of joyful perseverance. Seeing that dog each day became the highlight of my Maui morning walkies.

As they always must, eventually our vacation came to an end. Will and I returned home. Back to our lives.

In the decades since, I have come to believe that I died during that trip to Hawaii. Somewhere on that beautiful beach in Ka’anapli. I passed on. And that’s OK. My death was calm and mostly without pain. At the time, I was not even aware that I was dying. My transition was slow and unassuming. It likely took days. Starting from the moment I was told that I was down to only 38 T cells. A leisurely demise. My existence, as it had been up to that point, gently diminishing during those pre-dawn walks along the dark shore. It was a good death. A necessary death. And by the time I left paradise, all that I was and all that I believed in was irreversibly transformed. It had to be. The man who landed in Maui was clinging to a quickly failing life raft. The man who returned home had peacefully resolved to let that life raft go. And I did. I sank. And it was amazing just how different things became just below the surface. It was a magnificent world completely altered. Shimmering. Surprising. Serene.

Shimmering. Surprising. Serene… Your such a great writer… As always thanks for sharing!

lv

VW